We Can’t Let “Experts” Decide the Morality of Making “Humanized Animals”

Originally published at National Review- Categories

- Bioethics

Bioethics is a utilitarianish social-political movement whose primary advocates are usually philosophers, lawyers, and/or doctors. Mainstream bioethicists (unless they have a modifier in front of the identifier, such as “Catholic”) generally push against human exceptionalism — a concept many view as “speciesism” — and promote Tower of Babel–like experiments that push us toward an almost-anything-goes research ethic.

Bioethical issues are generally debated beyond the public’s perception, in professional journals, before they are introduced in public policy. The Journal of Medical Ethics, published out of Oxford, is one of the movement’s most influential publications. A major new article therein discusses the ethical implications of scientists’ implanting human-brain “organoids” — functional brain tissue created with stem cells — into animals, which could enhance their mental capacities. From, “Animus: Human Embodied Animals” (citations omitted):

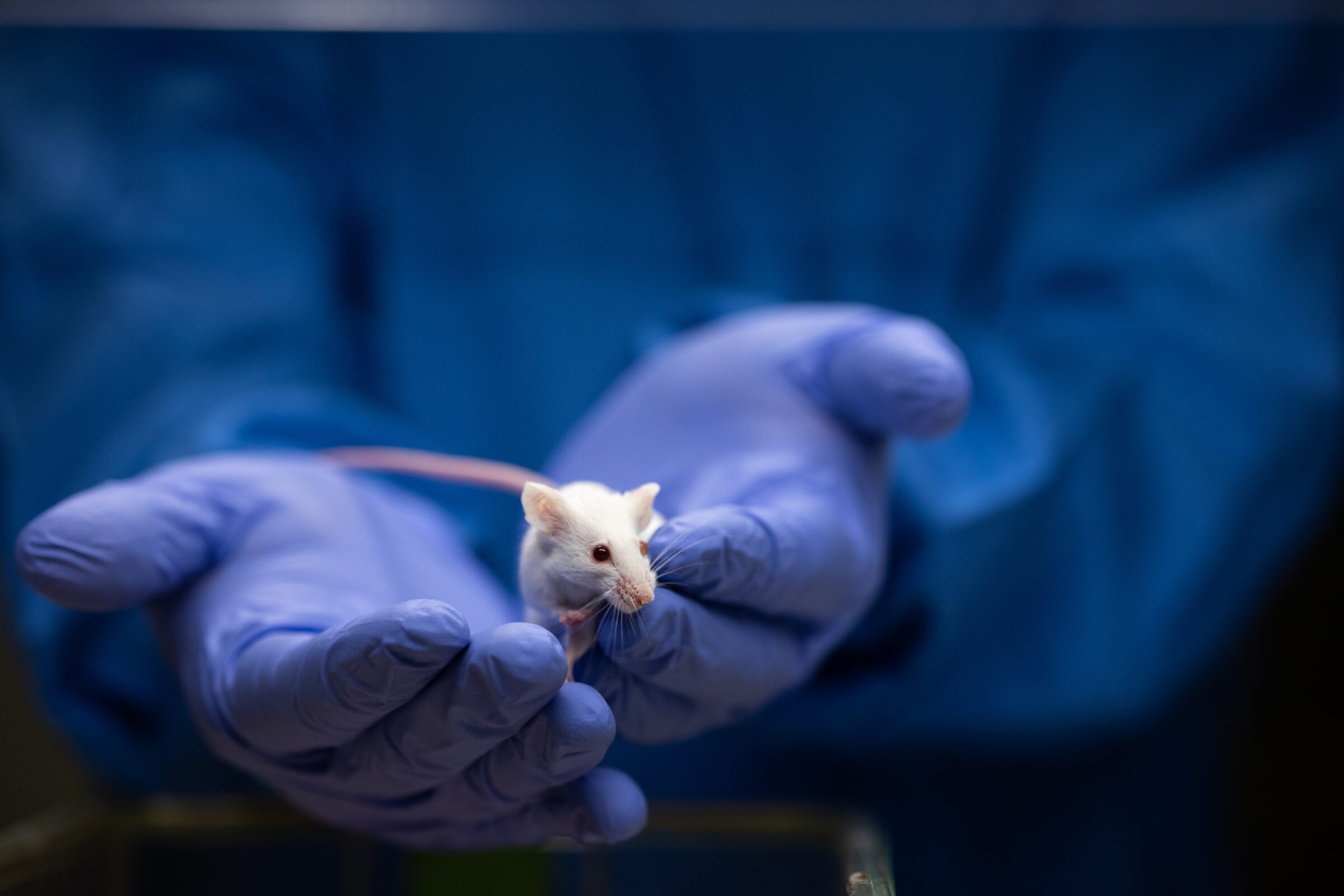

Recently, Sergiu Pașca, a leading scientist in the field of brain organoid research, along with his research group, has achieved a noteworthy milestone by successfully transplanting human brain organoids into rats. They have shown that these human brain organoids integrate into the rat brain and function, even being capable of affecting the behaviour of rats. Up to one-sixth of the rat cortex was human. In terms of their biology, these are ‘humanised rats’.

The idea that perhaps such experiments shouldn’t be conducted at all isn’t even considered by the bioethicists, who tend to cite the usual justification for radicalism in science, such as that human diseases could be eventually ameliorated by the findings of such experiments. They are concerned with setting “new standards for future research,” and the moral status of humanized animals should be accorded.

There are two kinds of such animals discussed: animals in which neural function is not affected (such as, say, a pig with a humanized kidney for use in transplantation medicine), and animals with modified brains that enhance their intelligence. To these bioethicists, function is the key:

The origin of a neuron, brain or person does not matter morally. It does not matter whether they are natural or artificial, carbon based or silicon based. Their anatomy or structure does not matter. Their appearance does not matter. What matters morally is function.

This is a bioethics belief that I call “personhood theory.” In this view, what matters morally isn’t whether one is human but whether one possesses relevant cognitive capacities such as self-awareness. Passing capacity muster — be it human, animal, or AI — makes one a “person.” Those who fail — including humans — are nonpersons that (not “who”) have lesser value. Personhood theory would destroy universal human rights and equality because some of us would be deemed of greater value than others.

Back to our humanized animals (what bioethicists are really talking about are personalized animals) — we could soon see human consciousness engineered into an ape:

If brain organoid research were to progress and substantial parts of key areas of, say, primate brains were replaced. If this replacement results in self-consciousness at the site of transplantation, or if the consciousness of the transplanted human brain organoid coexists with that of the host primate brain, we may confront a daunting ethical dilemma: the existence of human consciousness within a primate’s body.

The authors worry that if such an animal becomes conscious in the human sense, it could be wrong to experiment on or kill it. But how to know? Experiments! Which would manufacture them into being and create the very ethical dilemma under discussion. Sheesh.

But how to regulate what is right and wrong? Let the “experts” decide:

One kind of force which could have international penetration is peer or social pressure. Scientific bodies and journals could refuse to publish or acknowledge unethical research.

One example is the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) including leading scientists in the field. This body has been a leader in the field, including the service of professional ethicists. It has been proactive, providing regularly updated guidelines which include consideration of ethical issues.

The ISSCR produced updated guidelines in 2021. . . . Importantly these guidelines are already out of date. They eschew the possibility of organoids being conscious. . . . But these chimaeras are clearly conscious so at very least organoids are contributing to a conscious brain.

What a farce. The International Society for Stem Cell Research is justifying an almost-anything-goes approach to experimentation. For example, it once published ethical guidelines — the “14-day rule” — that limited the time during which experiments could be conducted on human embryos. At the time, embryos couldn’t be maintained beyond that point, so nothing was really being regulated or prohibited. Predictably — and I did predict it — as soon as the science advanced to the point where embryos could be maintained for longer periods without implantation, the ISSCR junked the 14-day rule. There is now no time limit, under ISSCSR guidelines, on experimenting on unborn human life.

An accompanying editorial from the JME argues in support of freedom for bioethical debates:

Bioethics journals play a crucial role in this, providing an important space for this reflective exercise to take place. There are (at least) three important dimensions to this. The first involves identifying the ethical issues raised by these emerging technologies. The second, debating these issues, with journals providing an important forum in which disagreement and debate can play out on how to respond to them. Only once reasoned views have been formed on these morally contentious issues can these then be used to inform the development of tangible public policy or regulation — the third important dimension.

It is the debate over these contentious issues that has come under threat in recent years, with increasing pressure to avoid engagement with ideas deemed ‘unpalatable’ from a misplaced fear that debating the issues simply serves to give oxygen to (allegedly) unacceptable views. Within this context, bioethical journals and their publishers must strive to ensure that they continue to provide a space in which all views on these issues are explored and debated however controversial or morally questionable they may be. The best way to confront immoral or mistaken viewpoints is to challenge the errors and presumptions that underpin those views. Abdicating from, or worse silencing, dissenting voices is a dead end.

The answer to bad speech is, indeed, better speech. But notice: There is nothing in the editorial about inviting the wider society into these discussions. It’s all about the opinions expressed in the journals toward achieving “consensus.” When that happens, the consensus is often imposed on public policy.

And therein lies the rub. The moral values that predominate within bioethics are not shared by a large percentage of the people who are supposedly served by this field. Indeed, when the editorial worries about the “silencing” of dissenting voices, I believe what it really worries about is public pressure from those of us outside the field who are rightfully disgusted by what passes for learned discourse in it.

Yes, we need expertise as part of these conversations and debates. But bioethics is an entirely subjective enterprise. Those claiming the mantle are not professionally licensed as bioethicists. One need not be a learned academic to have valid opinions about what is right or wrong.

We can’t allow policies about some of the most powerful and potentially dangerous technologies ever invented to be left to the supposed moral “experts.” The history of the last century or so illustrates the acute dangers associated with that approach.